2020 Director’s Close Up: Week Four

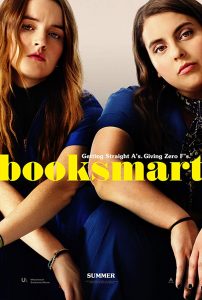

How does a director make a film? How has filmmaking changed? Week Four of Film Independent’s Director’s Close Up answered those very questions. The panel featured Lorene Clermont-Tonnerre (Writer/Director of The Mustang), Alma Har’el (Director of Honey Boy), Lorene Scafaria (Writer/Director of Hustlers), Lulu Wang (Writer/Director of The Farewell) and Olivia Wilde (Writer/Director of Booksmart). All films share one common feature, a visible passion for the story being shown. Yet, to get to that stage requires dedication and painful patience.

Filmmakers must first choose what topics to bring to the big screen. Many take inspiration from the real world. Scafaria’s The Hustlers transforms an article on a criminal ring into understandable and relatable individuals. Wang’s The Farewell shows Wang’s true family tragedy and Har’el’s Honey Boy visualizes Shia Lebouf’s dark and painful past as a child actor.

Whatever the topic may be, filmmakers must also ensure that investors feel the passion they do. For Wang, this took many, many years as The Farewell features a runtime almost entirely in Mandarin and a set almost entirely in China. This made any investor believe the film should be produced by a Chinese company, despite being from the perspective of an American. Scafaria had other issues in making Hustlers. After Scafaria’s script had been approved for production, it took close to a year to convince executives to even consider allowing Scafaria to direct the script she wrote.

The challenge of making a motion picture has only begun once production begins. Wilde’s Booksmart featured many Steadicam shots with very few cuts. That meant every actor shown on camera had to recite as much as “four pages of scripts” at once, as well as every aspect of blocking and rhythm. For The Farewell, the problems only begun at long shots. Because the film’s production took place predominantly in China, many cultural contrasts became quickly apparent. China had no way to shut down streets, meaning production had to occur in public as individuals walked in and out of frame. Assistant directors (ADs), who traditionally keep production on schedule, have different roles in China. The film features scenes in Mandarin and English, so most actors and most of the production crew needed to speak both languages fluently. Other productions may have to struggle with animals – with The Mustang featuring dozens of horses and a lead actor who could not ride horses. Other films have to cast and write children into highly adult-oriented scenes, as Honeyboy did.

After editing, coloring, VFX, sound editing and so much more has been completed, the director sits down with the composer to create the music for the film. Some films create stunning original soundtracks, others license them from modern artists. Some filmmakers decide to go to the music of centuries ago, as Scafaria did by having the The Hustlers score consist of music composed by Frederic Chopin, the 1800s pianist and composer. Sadly, Chopin’s genius requires the most talented pianists and, because of that, few recordings exist. So, production went on a copyright-riddled Easter egg hunt of trying to hunt down Chopin pianists to acquire rights for his treasured pieces. Wang’s The Farewell has classical pieces as well, which made sense as Wang then revealed she has a background in Classical piano – specifically Chopin.

While cinema has always had the passion and talent seen today, change can be seen in every way. The process of production has become faster and faster, with some panelists quoting 60 day production schedules or even 29 day production schedules. The lengthy steady-cam shots seen in every film featured would not be possible without modern stabilization technology. Har’el’s Honeyboy incorporates Wi-Fi-powered lighting setups, allowing the gaffer to turn on and off lights while a scene occurs, giving far more flexibility to the cinematographer and director.

Most of all, filmmaking has changed socially. This panel consisted entirely of female directors, a sight that could never be seen twenty years ago, and a sight that shall become increasingly common as the next generation of filmmakers make their first films.

For more information on Film Independent, go to https://www.filmindependent.org/

By Gerry O., KIDS FIRST! Film Critic, Age 17